Fascia: how to get your jive swinging & the sweetness of stress

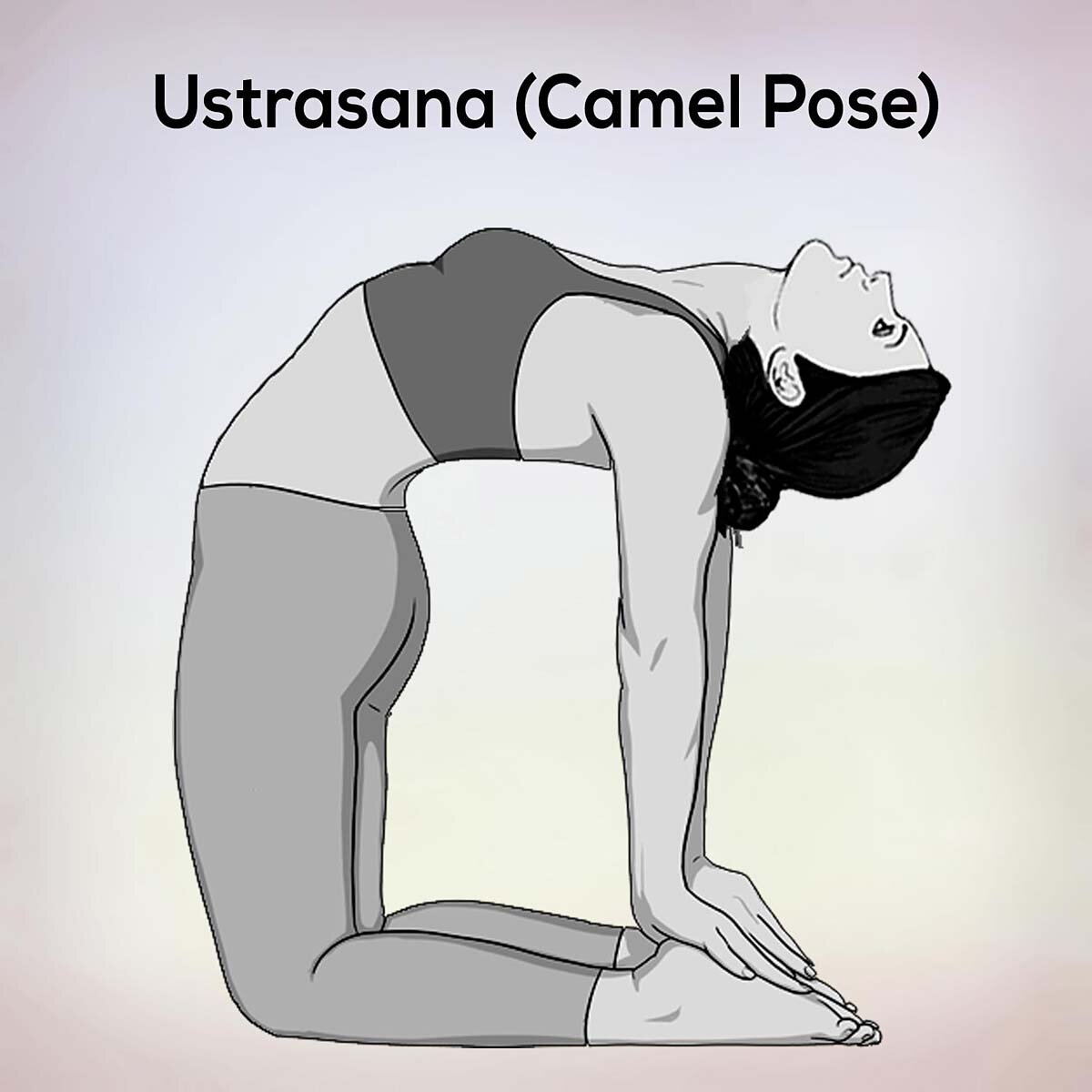

Why are we still saying that particular yoga poses are good for fascial release? Despite there being no evidence to support this spurious notion, it is a common assertion. For instance, I recently read an article stating that ustrasana, camel, is a good posture to release tight fascia. However, in making this assertion, it seems that we are treating fascia the same way we often treat muscles; as a discrete thing that is separate from the rest of our body, including our nervous system. This is even less true for fascia than it is for muscle. Fascia is extremely well innervated; with both myelinated and un-myelinated sensory nerve endings. Along with pressure sensors, these nerves help us know where we are in space; making fascia the main organ of proprioception.

Rather than being composed of discrete segments, fascia is one continuous tissue that runs throughout the whole body. It gradually changes as it’s relationships to the structures and organs it meets varies. However, there is no definable end to visceral fascia and beginning to deep fascia; just a gradual change in the properties of the same fascial tissue. The plantar fascia in our feet is not separate from the dura mater fascia surrounding our spinal cord and brains. If those were separate fascial tissue, it would not be so useful in helping us perceive where the whole of the body is in space. The brain needs to be able to sense where the feet are, and the feet need to relay sensory input back to the brain via the spinal cord. Exploring how fascia functions as an organ of sensory perception, helping us gauge where we are in relation to the world around us, can aid our understanding of why the idea of a single posture being useful to release ‘tight’ fascia is fundamentally flawed.

Fascia is a self organising supportive structure that helps a person carry out their intentions. It organises itself around our movement patterns and motor synergies. And they organise themselves around our nervous system. The old adage “neurons that fire together wire together” suggests that the more we do a task, the easier it becomes because those pathways get more clearly defined. So if we do a posture, any posture, with our habituated movement pathways, whatever we do will reinforce these neuromuscular pathways, rather than effect any change in them, or our movement. If our neural pathways and movement patterns are not changed, the way fascia organises itself cannot change either. To elicit a change in fascial organisation, we need a behavioural change. Unfortunately, such a behavioural change might not be possible while we are under the impression that fascia can be released by holding certain asana. We need to change the way we think about fascia first, so that we can change the way we approach our asana.

The idea of ‘releasing' fascia, is similar to the idea that we can 'stretch' a muscle. It can be done. It might even feel quite good or different for a short while. But, unless the way we do things is altered, any movements or postures that we do will result in us going back to the patterns of behaviour that caused the tightening of the part that feels like it needs to be ‘released’ or ‘stretched’ in the first place.

However, if we change the way that we do any posture, we will lay down different neuromuscular pathways. The fascia will organise itself to support those new pathways, and then change will occur. That will happen in any posture. No specific posture will give us any advantage over another.

Sorry, but I'm going to insert one of my favourite bad jokes here. Remember the wise words of Swami Bananarama 'it ain't what you do its the way that you do it, that's what gets results'. 😉

When we think about the amount of effort required to practice and achieve certain advanced asana, even more of the song is pertinent; 'you can try hard, don't mean a thing, take it easy, then your jive will swing'. So, if we keep approaching postures with an intention to achieve them, and we give some value to achieving them well, such as ‘releasing tight fascia’, the fascia will not be able to release, because we are approaching the task with all of our usual ‘let’s try hard’ neurons firing up all of our usual ‘let’s try hard’ muscular pathways. In other words, our fascia will organise itself around our core neurological programming of ‘let’s try hard’.

The mechanics of getting your jive to swing, sorry, your fascia to release, lies in changing the way we do asana. Take Swami Bananarama’s example; instead of trying hard, we could take it easy, and approach the posture in a far more relaxed way. For us to be more relaxed about this, we have to understand that it is not the posture that is the thing which is going to release the fascia, it is our attitude towards the posture that will lay down the new neuromuscular pathways that have the potential to release the fascia.

To put it another way, if we believe the particular shape we are making holds the key to stopping our pain and suffering which is caused by ‘tight fascia’ we are always going to revert to try hard mode because we really want to not feel pain. However, if we can change the way we think about fascia, and understand that it is our nervous system moving into ‘try hard’ mode that is the cause of the pain, perhaps we can approach our asana differently?

It sounds easy enough, but when we are used to looking at parts of us as separate pieces, we start to think about ourselves mechanistically. And when we are in pain, we really want an easy way out of pain. Unfortunately, if we have been in try hard mode for a few decades, the easiest thing for us to do is to try hard, because those are the neuromuscular pathways that are most regularly used. But, when we stop trying hard, and approach our asana from the stance of taking it easy, the fascia will organise itself around our intention to take things easy.

Is it possible to take it easy when doing camel? Maybe, for a very small proportion of the population. Only about 3% of people are hypermobile, and not all of them will be hypermobile in the particular way that allows them to easily and calmly ‘do’ camel. For most of the population, camel is an extremely difficult and indeed potentially dangerous posture that can only be approached from a place of striving to achieve or bracing against damage, both of which fall under the heading of ‘trying hard’. So that's what the fascia will do.

OK, it might be bracing against damage in a different place to the place that you habitually brace against damage; it might even elicit some short term feelings of release. However, unless you are going to walk around and go about your everyday life in a deep backbend, those feelings of release will be short lived because we will revert back to our usual ‘try hard’ movement patterns in our everyday life, and our fascia will rearrange itself around them again. Before long we will find ourselves feeling the need to ‘do’ camel again. Perhaps this is why some people feel the compulsion to do certain postures over and over again? This is one solution, but it is a solution that will keep us in a vicious cycle of fighting against our own patterning by trying hard, which is most likely the neurological pattern that created the problems in the first place. We will be treating the symptoms, but not addressing the cause of the issue.

A common area for us to blame ‘tight’ fascia for our pain, is often the thick diamond shaped thoracolumbar fascia in the low back. Would the extreme backbend of camel really help reduce tension there? Well, there is the pandiculation hypothesis (see 19/1/17 blog ‘Yoga is not Stretching’). If we introduce a pathway of increasing tension into an area that is already tense, we also create a way of the nervous system recognising a pathway for releasing tension, once we stop adding tension to it.

However, if we tell people that the shape called camel is the thing that will help, rather than explaining to them that it is feeling the release of tension when we come out of camel that can help, they will not know why they are doing what they are doing. So instead of recognising the subtle, soft sensations of release as the sensation we want to follow, we are likely to follow the more obvious sensation of creating more tension. This explains how we get hooked on chasing that feeling of creating more tension, commonly known as stretching. Plus, when we damage ourselves, pain killing hormones are released and these can be quite addictive.

Fascia is chemically sensitive. It responds not only to our nervous system and movements patterns, but to our brain and body chemistry. Therefore, hormones can alter our fascia’s tone and properties. It is well documented that women are more prone to fascial complications than men due to fascia containing oestrogen receptors that cause laxity in ligaments not just around areas that need to be more forgiving for pregnancy and childbirth, but these receptors are also found in the knees and feet, contributing to increased instances of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries and plantar fasciitis in women compared to men. One of the interesting snippets of information I learned whilst teaching yoga to footballers is that women footballers have a greater incidence of ACL injuries than male footballers, and that this increases even more at certain times of the month. But, when researching how pain reduction and stress hormones affect fascia, it is more difficult to find research presenting primary data. Strange, as footballers are much less plentiful than people suffering from chronic pain.

Pain is felt in the nervous system, rather than in the damaged tissue. It is the body’s way of bringing into our conscious awareness what is going on in our tissue. However, we can get stuck in a chronic pain cycle when we mistakenly equate our felt sensation of pain with tissue damage. Understandable, given that prevailing models of pain and its relief do not take into account the extent to which the way we think about pain can cause us to either up or down regulate it; thereby increasing or decreasing the sensations that we feel. Or, if we do take into account our psychological ability to intensify or negate the sensation that we feel, it is presented in such a negative way that we fail to account for social and cultural input into this. All too often, we lay the accountability for chronic pain on the individual, rather than the systemic. We once did this with female footballers. They were often told they were up regulating or exaggerating their pain, on account of being women, rather than on account of their having much less stable connective tissue than men; a biological system issue. This was reinforced by them being in a sport with a pronounced patriarchal culture, sometimes quick to label them as overly sensitive or emotional.

This way of thinking still prevails as often when presented with chronic pain, we more often than not look for answers in the tissue. I’m not saying that we should not look for answers there. We definitely should! To ignore that there might be damage there would be to negate the experience of the person feeling the pain, not too mention the fact that quite often the nervous system is alerting us to the presence of tissue damage through pain. But when we do not find the answers we seek in the obvious tissues, we keep looking for them in increasingly less obvious places. Again, completely understandable and necessary.

Pain is often attributed to fascia when all other avenues of enquiry involving tissue damage have been exhausted. By this point, pain has usually become chronic. Long lasting, chronic pain causes a great deal of stress. One of the effects of prolonged stress is an increase in cortisol levels, which in turn raises blood sugar levels, as cortisol releases stored sugars in anticipation of us reacting to the stressor by running away or fighting. Both activities require a great deal of muscular effort, and muscular effort needs sugar.

Shanahan, et al (2020)

However, oftentimes we do not respond to stressors by utilising this released sugar energy, and unfortunately, when sugar accumulates in our blood, it causes inflammation, which releases more sugar, and the presence of too much sugar hardens our fascia. Fascia is primarily comprised of collagen. Although collagen needs sugar to form supportive structures, called fibrils, it can only do this in the presence of the enzyme lysyl oxidase. Too much sugar can cause sugar to bind to collagen without the mediating effects of this enzyme, which arranges sugar molecules so their hydrophobic side is facing out. In the absence of lysyl oxidase, sugar binds to collagen with its hydrophilic, water loving, side facing out. Instead of being able to hold the surrounding water at bay so collagen and glucose can form smooth fibrils, along the lines of tension required for us to act out our intentions, the hydrophilic face of excess sugar disrupts the hydrostatic forces, already increased by inflammation, causing irregular fibril formation, which stiffens our fascia.

Therefore, it could become more difficult for our fascia to arrange itself around our intention to move in a particular way, causing our movement pathways to become less efficient, and contributing to a distorted view of where we are in space, or diminished proprioception. This is evident in the pathology of diabetes. By this rationale, when we are under stress, in chronic pain, or suffering from chronic inflammation, our movement pathways can be distorted.

In order to learn new ways of doing things, we have to unlearn our old ways. Unfortunately, when we are in pain, we tend not to get much sleep, and sleep is essential in undoing old neurological pathways. Our immune system functions much better when we are well rested. Our immune system does not only protect us from bacterial and viral attack, it also carries out a lot of general housekeeping. When we sleep, macrophages detect and destroy harmful substances, such as waste materials, like excess sugars & other free radicals. So good sleep will improve our ability to lay down well formed, hydrophobic fascia.

Sleep also helps physically clear our brains. The synapses of neural pathways that have not been used for a while get marked with a protein that our brain’s macrophages, or microglial cells, love to eat. OK, they don’t strictly eat them, but these microglial immune cells act as neurological housekeepers, bonding to the protein, absorbing it and the unused synapse. These microglial cells act as the detritivores of our brains. They leave pathways that get used intact and clear away all the old pathways, leaving us able to think more clearly. Perhaps then, we can choose which neural pathways we want to get cleared away by practising the neural, and subsequent neuromuscular pathways that we want to keep?

In conclusion, to release an area of fascia that feels tight, perhaps all we need to do is find something that we can do easily to practice. Some movement so small, so pain free, that we can practise it over and over again without trying hard, even if it looks like we are barely moving at all. Anything that brings our nervous system back into rest and digest, so we can get some good quality sleep, so we can let go of those old pathways of fight and flight.

Maybe all we need to do is less and less, until we get to a place of effortless effort or as Patanjali puts it in Sutra 2.47 “Prayatna-shaithilya”. But to do that, its not helpful to be overly attached to the fruits of our labour (Bhagavad Gita 2:47), as that might make us revert to trying hard to achieve them again. Maybe our understanding of anatomy, neuroscience and cellular biology is finally catching up with yoga philosophy?

Bibliography:

Bansode, S et al (2020) Glycation changes molecular organization and charge distribution in type I collagen fibrils (Nature) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-60250-9

Besedovsky L., Lange T., Born J., (2012) Sleep and immune function (Pflugers Arch.) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3256323/

Bordoni, B, Mahabadi, N & Varacallo, M (10/8/20) Anatomy: Fascia (National Center for Biotechnology Information) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493232/

Garofolini, A & Svanera, D (2/8/19) Fascial Organisation of Motor Synergies (European Journal of Translational Myology) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6767996/#:~:text=The%20function%20of%20the%20fascial,speed%2C%20in%20the%20same%20direction

Kabba, JA et al (1/2018) Microglia: Housekeeper of the Central Nervous System (Cellular & Molecular Biology) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28534246/

Nordin, CR (2020) Stress and Sugar Harms Fascia Functions (The Fascia Guide) https://fasciaguide.com/problems-linked-to-fascia/stress-and-sugar-harms-fascia-functions/

Petrofsky, J & Lee, H (2016) Influence of Estrogen on the Plantar Fascia (Lower Extremity Review) https://lermagazine.com/article/influence-of-estrogen-on-the-plantar-fascia

Shanahan, C et al (2020) Collagen Glycation and Diabetes (University of Cambridge) https://www.ch.cam.ac.uk/group/duer/research/collagen-glycation-and-diabetes#:~:text=Collagen%20is%20naturally%20glycosylated.,do%20not%20form%20structural%20fibrils

Tang, M et al (10/2020) Effect of hydroxylysine-O-glycosylation on the structure of type I collagen molecule: A computational study (Glycobiology: Oxford Academic) https://academic.oup.com/glycob/article/30/10/830/5809505

Yeager, A (1/5/20) How Immune Cells Make the Brain Forget (The Scientist) https://www.the-scientist.com/notebook/how-immune-cells-make-the-brain-forget-67475